spiritual lingo and god as literary character

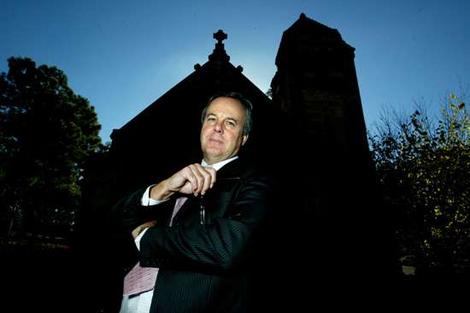

Though I'm meant to be avoiding the subject of George Pell, I was quite amused by these musings.

Now, to add something to my comments on spirituality written elsewhere. One of my pet peeves is the use of spirituality lingo to castigate or demean those thinkers who don't demonstrate much interest in said lingo. For example, I recall being infuriated years ago when I read a literary critic comparing one of my favorite writers, Stendhal, to Lev Tolstoy. He claimed that the 'spiritual dimension' to Tolstoy's work gave it a depth which Stendhal's work lacked. The lack of any developed argument behind this claim angered me perhaps more than the claim itself. In any case, Stendhal's low key approach to the emotional storms of his characters creates resonances for me that are powerfully moving, and if he lacks anything in comparison to Tolstoy it has nothing to do with the 'spiritual dimension', IMHO.

A similar claim was made more recently on a radio program in which Peter Singer and Raymond Gaita were compared as prominent Oz philosophers, and wouldn't you know that Singer's non-belief made his moral philosophy just too 'thin' and coldly rational for these experts. Again no elaboration on such a questionable claim. No mention of a predisposition to find people of faith magically possessed of a deeper, richer more comprehensive view of the world.

To mark my continuing interest in faith-based belief, a friend has bought me a book. It's called God: a biography, by Jack Miles. Of course this gift was given me in the spirit of irony, and I looked forward to finding plenty of irony in the book (the author's streetwise-sounding name seconded the promise), but on the contrary it's a tome that takes itself all too seriously.

Still, the first thirty pages or so are fascinating. Miles comes from a tradition of secular Bible scholarship, and it's impossible so far to be sure about where he stands in terms of faith. I doubt if I'll be any surer by the end of the book, and that's certainly not my way, I have to nail my colours to the mast from the outset. Yet there are some advantages to Miles's method. People of faith are going to find less to object to, probably, than they'd find in the work of an avowed non-believer, and will be drawn into wondering about the inconsistencies and oddities of this God character, while the non-believer will find here plenty of fresh ammunition for the good fight.

He spends the first pages explaining and justifying how he's going to approach the issue. He claims that the Bible is generally regarded as literature by everyone, regardless of whether they see it as the revealed world of God, and that one key to great literature (he uses Hamlet as an example) is that their characters are felt to live beyond the pages of the text, so that these characters' characters, so to speak, can be analysed as fruitfully as if they're real people. This is an odd argument it seems to me - after all, we don't see too many bios of Hamlet, Don Quixote or Huck Finn on our shelves. And of course Miles stops well short of describing the Bible (or, strictly speaking, the Tanakh, for he's using the Hebrew Bible as his text) as fiction.

Be that as it may, he has chosen to write a biography of a character in literature, using that literature, and nothing beyond it, to get a handle on the character and his activities. This, though is a more slippery task than he acknowledges it to be, and it seems to me he gets in trouble right from the beginning. Naturally he begins with the creation of the earth, and notes that God appears to be talking to himself, since he's the only one present (though there is a narrator, a conundrum largely passed over). The first words, 'let there be light' are, incidentally, more brief and less commanding in the original Hebrew. Miles suggests that he's more like a worker talking to himself about what he's doing while he does it.

It's a blokes and sheds kind of thing. When a bloke's in his shed, he's in another world - he might have a wife and five kids but you'd never be able to infer this from watching him work. Similarly, in watching God in the throes of creation, we're unable to infer anything about his family background, and we're told nothing, either by God or by the narrator. To quote Miles:

The text speaks of God as masculine and singular. And if this God has a private life or even, as we might say, a divine social life among other Gods, he isn't admitting us to it. He seems to be entirely alone, not only without a spouse but also without a brother, a friend, a servant, or even a mythical animal.

Seems is an important word here. From our perspective, as his creations (according to this literary work), God is sole creator, but we have no way of knowing whether, when he retreats from us back into heaven, he has a goddess wife and lots of godly kids, or brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts. His creative acts make monotheism a reasonable response from a human perspective, but his singleness can't be inferred with certainty from the Tanakh, at least not from the early verses of Genesis.

Anyhow, an intriguing work so far, but, I would argue, not a biography. Rather it's a piece of literary criticism or analysis, with particular attention to the development of the most important character in the literary work, even if he remains in the background most of the time. As such, it dispenses with the essential question, whether God exists, and focuses on his possible motives and the development of his character within the literary work that's most concerned with him. As I have an honours degree in English literature, this approach is very familiar to me, and I've already received much pabulum from the first pages. I don't even mind the slightly false promise of the title. If it gets people in....